OFARTS History- by Stan

Fockner

I

became a member of the Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians

in September 2002. I have not been able to track down who actually established

this wonderful group but know its origin is founded on mutual respect, trust,

loyalty and friendships established during employment with the Department of

External Affairs, currently known as Foreign Affairs Canada.

I

became a member of the Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians

in September 2002. I have not been able to track down who actually established

this wonderful group but know its origin is founded on mutual respect, trust,

loyalty and friendships established during employment with the Department of

External Affairs, currently known as Foreign Affairs Canada.

OFARTS, in one form or another, is likely

older than dirt.

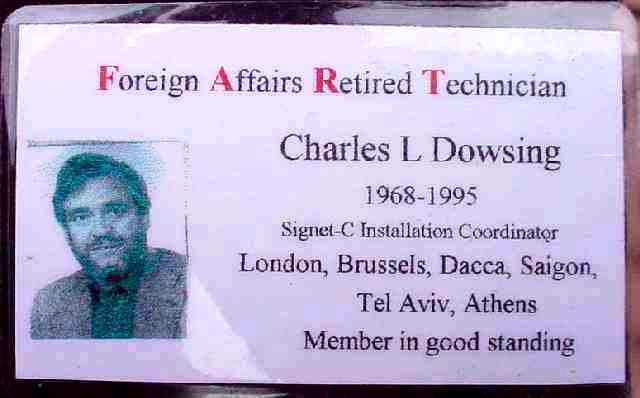

Charles (Chuck) Dowsing

used to prepare nicely laminated wallet-sized "membership" cards for

new retirees but the practice had stopped some years before my retirement. Chuck

claimed he did this as a lark but these cards are now prized keepsakes. I

suspect that Chuckles actually coined the OLD FARTS name.

I created the first Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians presence on the WWW

as a lark too, just after my retirement in 2002. The original web pages were

hosted by Rogers Communications who eventually "farmed out" their

e-mail to Yahoo and their "members" web pages to Geocities. Geocities

added pop-up advertising to create revenue and established user access

constraints which both annoyed and limited the number of visitors. But it was "free"

which was a concept novel to me and to many techs.

By September 2006 the Old FARTs Geocities web site was nearly

full of pictures, a good story contributed by Donald Graham (in self defense)

and obituaries. BUT, another tale written by Fred Snow just before he died, was

being edited by his widow Yvonne. The remaining web space was used to

accommodate the very fine finished product. "Passage

to India". in the Articles

section (formerly Story Land). And more techs were retiring and some needed

obituaries. A sad fact.

The response to Fred's tale was a real wake-up call: The Old

FARTs web site was no longer a lark.

Then, I was delighted to receive this message:

Stan,

At our last AFFSC Board Meeting the OldFarts web site was brought

up. We agreed that we would like to contribute the cost of

purchasing a domain name (ie oldfarts.ca) and offering our meager web

experience (Howie and myself) and assist in getting you working in some better

web space.

There's an offer for you!

Cheers,

George McKeever

The OLDFARTS.CA domain name had already been taken by an

"entrepreneur", so we settled on OFARTS.ca. This was acquired

and funded by the AFFSC, our communicator colleagues, on October 10, 2006.

The need for a "suitable" web host (read - cheap, reliable

and flexible) was met with the "Mini 2" package offered by

HostUtopia in Vancouver B.C. Canada. for $120 / year with nearly all taxes

included ! The account was activated on October 10, 2006 and I went to work

re-learning LINUX.

Unlike the AFFSC, the Old FARTS have never been "organized". We

generally agree that, in retirement as in work, we just don't like bureaucracy.

Never did.

Maurice

(Moe) Rainbow agreed to help with site administration

and began studying the "ins and outs" of web design after his

retirement in Ottawa and his move to Nova Scotia. Moe returned to Ottawa in

2008.

Maurice

(Moe) Rainbow agreed to help with site administration

and began studying the "ins and outs" of web design after his

retirement in Ottawa and his move to Nova Scotia. Moe returned to Ottawa in

2008.

Raymond

(Ray) Fortin is our secretary-treasurer for this

venture and is managing the contributions to defray the cost of the server which

is located in Vancouver British Columbia. Ray's current e-mail address is raymondfortin

(at) rogers.com . He assures me that contributions are still

arriving and that we went live "debt free" on December 1, 2006. Ray

has made many contributions to the photographic history of OFARTS Canada on

Jerry Proc's website. http://jproc.ca/crypto/canadian_comm_center.html

is but one example..

Raymond

(Ray) Fortin is our secretary-treasurer for this

venture and is managing the contributions to defray the cost of the server which

is located in Vancouver British Columbia. Ray's current e-mail address is raymondfortin

(at) rogers.com . He assures me that contributions are still

arriving and that we went live "debt free" on December 1, 2006. Ray

has made many contributions to the photographic history of OFARTS Canada on

Jerry Proc's website. http://jproc.ca/crypto/canadian_comm_center.html

is but one example..

James

(Jim) Rogers is probably responsible for the rapid

listing and relatively prominent standing of the site on YAHOO, GOOGLE and

NETSCAPE search engines: Jim quietly suggested the consistent wording used in

the footer on each page and provided the "robot friendly" text file we

use on the server to attract search engines. Jim has also scanned many of the

pictures shown in the retirement area and contributed to the many retirement

photographs..

James

(Jim) Rogers is probably responsible for the rapid

listing and relatively prominent standing of the site on YAHOO, GOOGLE and

NETSCAPE search engines: Jim quietly suggested the consistent wording used in

the footer on each page and provided the "robot friendly" text file we

use on the server to attract search engines. Jim has also scanned many of the

pictures shown in the retirement area and contributed to the many retirement

photographs..

Donald

(Don) Butt is credited with offering his Royal

Canadian Legion home as the place where

we meet. for lunch each Wednesday starting at 1100. Don was usually the first

to arrive at lunch and the last to eat. He made us feel very much at home.

Unfortunately Don entered hospital on October 31, 2007 with cancer and died on

July 7th, 2008. His memory lives with us all..

Donald

(Don) Butt is credited with offering his Royal

Canadian Legion home as the place where

we meet. for lunch each Wednesday starting at 1100. Don was usually the first

to arrive at lunch and the last to eat. He made us feel very much at home.

Unfortunately Don entered hospital on October 31, 2007 with cancer and died on

July 7th, 2008. His memory lives with us all..

Yours sincerely,

Stan Fockner

Stan Fockner

This site has now been

More History

By Terrance Storms in the Dorchester Review June 13. 2013

The Decline & Fall of the Foreign Service

All sovereign countries have a foreign service, a cadre of specialists in

international relations sent abroad to look after the country’s interests. The

British and Americans each have one, the EU recently created one, and the Holy

See has perhaps the oldest one.

It is the opinion of this author that Canada no longer really has one. That

is not to say that there are no longer dedicated and skilled specialists who

work to protect Canadians and Canada’s interests abroad. Quite the contrary.

There are still some tucked away in the Department of Foreign Affairs and

International Trade. It is not that there was some overt effort to destroy a

professional foreign service. Nonetheless, because of a combination of changes

in the civil service in Ottawa and, coincidentally, some societal changes in our

country, it is fair to say that a foreign service no longer really exists.

The origins of the Canadian Foreign Service lie in the early twentieth

century. Previously Britain looked after our international relations, even with

our closest neighbour, the United States. Before 1910, a section within the

Department of the Secretary of State under Sir Joseph Pope had the purpose of

managing what were called “Imperial relations,” that is with the mother

country and to a lesser extent within the Empire. The Government of Sir Wilfrid

Laurier created a separate Department of External Affairs in that year, over

which the Prime Minister presided as Minister, with Sir Joseph as its first

Under-Secretary of State, a post he held until his retirement in 1925.

For a time the Department remained minuscule but with steady growth of

Canada’s interests and responsibilities it became necessary to establish,

following the example of other nations, a functioning foreign service with the

background, training and skills to handle the foreign interests of Canada. O.D.

Skelton of Queen’s University followed Pope as Under-Secretary and set about

gathering a group of bright and talented young men for that purpose. This was

the so-called golden age of Canadian diplomacy: Pearson, Pickersgill, Heeney,

Wrong, Keenleyside and others were recruited to man the headquarters and a

slowly growing number of posts (and conferences) abroad. Largely anglophone,

upper-middle-class, English-educated (Oxford) and male, it was a small and

dedicated group.

The early 1970s represented both an apogee and the beginning of a decline. By

the early Seventies those associated with the original exclusive group had

passed from the scene. Pearson was gone, Skelton long gone; Vincent Massey, who

had gone on to greater things, had also been carried away. Time, that ever

rolling stream, had also born away Hume Wrong, Norman Robertson, Dana Wilgress,

Hugh Keenlyside and Arnold Heeney.

As the Foreign Service grew it remained a largely self-selecting group,

urbane, male, increasingly nationalist (anti-Imperial but not necessarily

pro-American) and, within the Public Service, a homogeneous and distinct group.

The original formula favouring English-educated anglophones with an enlivening

admixture of pure laine francophones had long been broken with the recruitment

of others, including a small but growing number of women. The overwhelming

caucasian dominance was also soon breached.

The brooding, dark permanence of “Fort Pearson,” the Lester B. Pearson

Building at 125 Sussex Drive, was still in the planning stages. Part of the

charm and mystique of the Department at the time derived from the disorganized

shambles of its location; it was scattered in over a half-dozen buildings across

the centre of Ottawa, including the East Block, the Wellington Street Post

Office, the Daly Building and a host of even less distinguished locations. But

this was the Department of the previous Prime Minister, L.B. Pearson — Nobel

Peace laureate, founder of peacekeeping and engine of the Canadian efforts which

contributed to the creation of NATO, etc.

A portent of what was to come was provided by the infamous cuts of the late

1960s which had seen officers fired for the first time under a reverse order of

merit scheme. It was traumatic for all and deeply remembered even thirty years

later, when those who had as junior officers been part of the personnel team

which carried out the cuts were recalled with some bitterness. About the same

time, the then Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, made some unamiable comment

(which one had hoped was apocryphal) that the New York Times provided him with

reporting more timely and profound than the Department’s.

A chastening note and portent of things to come was given in the appointment

of Allan Gotlieb (1928 – ) as Under-Secretary, i.e, Deputy Minister, in 1977.

Rumours were rife that we had seen the last Deputy who had made his way up from

the ranks of the Foreign Service. Gotlieb had had a brilliant career in the

Public Service outside the Department after starting in the Foreign Service and

serving abroad once in Geneva. He was to be one of our most distinguished

ambassadors in Washington. However, his advent was seen as the beginning of

changes to come and although there were Deputies appointed who had spent at

least part of their careers in the Foreign Service, such service was clearly no

longer a requirement. Trade Commissioners, Presidents of CIDA, Deputy Ministers

from Citizenship and Immigration, and most recently a public servant who made

most of his career in the private sector and in the Privy Council Office and had

no previous experience of the Foreign Service or the work of the Department,

have been appointed as Deputy Minister. This is not the place to make any

comment about their contributions to foreign policy or to the management of the

Department, but it does highlight the beginning of a separation of the upper

levels of management from the Foreign Service they directed. And more was to

come.

However, by the time of which we are speaking, the general spirit of the

Department was upbeat. It had survived wrenching cuts and was confident that it

would find an accommodation with its outside critics. Senior members of External

Affairs were found in jobs at the top of departments across the federal

government. In any event, the trend in bureaucratic growth was generally in the

ascendant — the public servant’s ultimate revenge then as now. The next

thirty or so years showed this optimism to be correct generally, even if less so

in its specifics.

The internal structure of the Foreign Service group reflected this history.

In 1971 there were (from top to bottom) ten FSO (Foreign Service Officer)

levels: 10 being the most senior level and 1 (probational) entry-level. Soon

after, the structure of the Foreign Service was collapsed to five levels under

what was called the FS group conversion. What was the reason for this change?

The most probable reason was economic. After a period of retrenchment, it was

also less complicated and less expensive to conduct five promotion board

exercises across the whole Department rather than ten. The change was not

without controversy, but the officers were offered a system with five salary

bands to cover the same range as had been separated by ten before.

One of the most dramatic turns in the history of the Foreign Service was the

decision to consolidate all of the parts of government departments having

significant representation abroad under the aegis of what became the Department

of External Affairs and International Trade. In 1982 the traditional Foreign

Service, the Trade Commissioner Service (itself with a distinct and quite long

history) the Immigration Service, and CIDA effectively became parts of one

administrative structure, their storied particularities reduced to four

dedicated employment streams: Political and Economic, Trade, Social Affairs, and

Development.

This action brought together into one Foreign Service structure (or group)

all of the government employees serving Canada abroad and thus committed to some

form of “rotationality.” This meant that these employees were committed to

working at least part of their government service in missions abroad. It did not

include, and was never meant to include, public servants from other Departments

who served in a small number of highly-specialized positions abroad on behalf of

the RCMP, the RCMP Security Service, National Defence (military attachés and

their support), National Revenue, the Department of Labour, the Secretary of

State, and the Departments of Finance, Transportation, etc., usually on a

single-assignment basis. In other words, they were an elite service apart from

the rest.

The 1980s also saw the folding together of large parts of the domestic (i.e.

Ottawa) structures of these now “unified” foreign services. Dedicated

positions (and by implication the funding to pay for them) were contributed by

the originating departments and a free-for-all followed whereby the services

competed or negotiated for paid positions in the new consolidated structure.

There was much horse-trading between the originating Departments and those

supposedly controlling the process (the Public Service Commission and Treasury

Board) as each sought to minimize the cost to their existing establishments and

the new parts of the Foreign Service looked to extracting maximum advantage from

the new structure.

This new structure worked with only limited success for a short period. The

Department of Immigration and CIDA eventually reasserted control over their own

positions and employees. The enduring part of the unsuccessful reform is found

in the co-location of the Trade Commissioner Service and the Foreign Service of

Foreign Affairs within the Department of Foreign Affairs and International

Trade. Although under one roof, the two services now operate in largely parallel

universes where the chimæra of consolidation manifests itself from time to time

at the very top of the Department (DFAIT).

At about the same time as the administrative feint of consolidation was

occurring in the 1980s, the Government for other reasons was effectively

undermining specialist professional groups (including the Foreign Service)

throughout the civil service in the interest of creating a common EX (executive)

group across the entire Public Service.

One of the motivations for this was to meet the Government’s commitments to

ensure employment equity for women, First Nations, persons with disabilities,

and visible minority groups. Another driving force was that the Government

believed that, as far as Foreign Affairs was concerned, at the management level

the particularities of the practice of diplomacy were something that could be

learned on the job and were in any case secondary to the requirement for a good

and equitable management cadre which mirrored the ideal of a thoroughly

representative, non-discriminatory and welcoming Public Service.

This was done incrementally over a number of years starting at the top. It

was also a real body blow to the Foreign Service. Peeling off successive levels,

they not only reduced the size of the FS group but diluted the commitment at

senior levels to the idea of a professional diplomatic service.

The Professional Association of Foreign Service Officers (PAFSO) was left to

represent mid-level and junior members only. Although the Department retained

the services of significant numbers of these new EX officers, it can be asked

whether they continued to see themselves as part of a Canadian diplomatic corps,

especially as their pecuniary and professional interests were managed from

outside the Department.

One of the unintended consequences today of a remnant FS group is that they

increasingly regard themselves (and their professional association) as a

militant bargaining unit. The author, as a management exclusion, has on a number

of occasions had to wend his way gingerly past unhappy colleagues on the picket

line. This is a function of the separation felt by FS Officers from the

leadership of the Department.

Why was it done? One can question whether it was done with the explicit

intention to destroy the Foreign Service. It is plausible that, given the desire

to achieve employment equity across the government, this motive was not even a

primary consideration. The FSO/FS group was in the attitude of the day no more

important than any other employment group. However, in the course of this

lengthy process, the Department was rife with rumours about the animus against

the Foreign Service because of its closed system. In the past the Department had

always fought tooth and nail to prevent lateral or any other transfers into its

ranks. This perception could well have fed the process.

Changes in the wider social ethos also played a role. In 1958, Margaret

Meagher was appointed as the first female Ambassador. Women were not recruited

as officers in the Department until after the Second World War. Married female

officers were not allowed until the late 1960s, before which the practice also

meant that the female partners in officer couples had to resign. The first women

heads of mission and senior officials in that period were unmarried. This

situation clearly had to change to reflect, even if somewhat tardily, practices

more generally in Canadian society.

Staffing challenges in the new environment have included the rise in the

numbers of “employee couples” and of the numbers of employees whose

spouses’ professional situation had to be accommodated. The Officer with a

spouse working as a homemaker and hostess became increasingly rare. Posting

married officers was difficult enough. Missions abroad are small and positions

at appropriate levels were difficult to find under the best of circumstances.

These problems were exacerbated once the normal, uneven course of careers

unfolded, and spouses could not work in a hierarchical relationship without

running up against accepted practice concerning conflict-of-interest while

possibly devastating the office work environment. Spouses from different

departments posed even greater problems as one of the two had to seek a

temporary release from work. Sometimes work for the non-departmental spouse was

available at the city where the assignment took place (in an international bank,

an NGO or simply in the local business environment) but often it did not, or at

least no assurances could be given to the person looking to continue working

during the period of interruption. Whatever the case, reluctance to accept

assignments abroad has grown, making personnel management within the Foreign

Service increasingly complicated.

In response to all these limitations on the assignment process (and perhaps

because of the reduced significance of the Foreign Service as an institution)

the Department has opened up all assignments at headquarters and abroad to

federal employees across the Government. This attenuates even further the

importance of a cadre foreign policy specialists whose importance numerically,

as we have seen, has also been in decline. The longer-term impact of such a

policy can only be devastating for the working end of the foreign policy

establishment.

To recapitulate, in 1971 there were ten FS levels. For a considerable time

after the reduction of its senior members, there were two levels left: FS-01 and

FS-02. With the hiving-off of the whole of the management cadre (EX1 to EX5),

what was left were the workers: officers and specialists but not “managers”

(although in missions abroad they were often managers of significant numbers of

other staff). More recently, there has been the addition of two further levels

(FS-03 and FS-04) to reflect mid-level (but not specifically managerial)

responsibilities and levels of professional, linguistic and area

specializations. Salaries at the top level overlap with the EX-01 level,

offering a small bone to Foreign Service professionals who would otherwise see

their remunerative prospects running out at a relatively modest level.

The coup de grâce to the Foreign Service remnant has been the opening up of

jobs at all levels to competition (or application) from the rest of the Public

Service. This began at the EX-level positions but is now the case across the

board, including at support staff levels. As a result, anyone recruited to the

Department at the entry level with high ambitions sees the remaining FS group as

a place of transit, where one can work in the substance of international

relations while looking to move on and up. To these transitory FS officers may

be added others from outside who might consider an assignment in the Department

at headquarters or abroad as an interesting stage in their personal career

without any kind of commitment to the Foreign Service. Some are actually now

able to enter laterally for a second career in DFAIT having grown bored with

Public Works or Revenue.

The occult process whereby this took place had been long and complicated.

Throughout, there is little if any evidence that the management ever sought to

defend the Foreign Service against the attacks that resulted in its reduction to

a remnant of what it was. Whether this has been good or bad for the Department

or the remaining diplomatic “practitioners” is hardly relevant anymore. The

changes have been so pervasive and anchored in the way that the Public Service

is managed generally, that it seems impossible to imagine any other reality. It

is too late to go back. The world and governments have moved on, and the Foreign

Service is no more.

© OFARTS Canada 2006-2007 Old Foreign Affairs Retired

Technicians, Canada

I

became a member of the Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians

in September 2002. I have not been able to track down who actually established

this wonderful group but know its origin is founded on mutual respect, trust,

loyalty and friendships established during employment with the Department of

External Affairs, currently known as Foreign Affairs Canada.

I

became a member of the Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians

in September 2002. I have not been able to track down who actually established

this wonderful group but know its origin is founded on mutual respect, trust,

loyalty and friendships established during employment with the Department of

External Affairs, currently known as Foreign Affairs Canada.

Maurice

(Moe) Rainbow agreed to help with site administration

and began studying the "ins and outs" of web design after his

retirement in Ottawa and his move to Nova Scotia. Moe returned to Ottawa in

2008.

Maurice

(Moe) Rainbow agreed to help with site administration

and began studying the "ins and outs" of web design after his

retirement in Ottawa and his move to Nova Scotia. Moe returned to Ottawa in

2008. Raymond

(Ray) Fortin is our secretary-treasurer for this

venture and is managing the contributions to defray the cost of the server which

is located in Vancouver British Columbia. Ray's current e-mail address is raymondfortin

(at) rogers.com . He assures me that contributions are still

arriving and that we went live "debt free" on December 1, 2006. Ray

has made many contributions to the photographic history of OFARTS Canada on

Jerry Proc's website.

Raymond

(Ray) Fortin is our secretary-treasurer for this

venture and is managing the contributions to defray the cost of the server which

is located in Vancouver British Columbia. Ray's current e-mail address is raymondfortin

(at) rogers.com . He assures me that contributions are still

arriving and that we went live "debt free" on December 1, 2006. Ray

has made many contributions to the photographic history of OFARTS Canada on

Jerry Proc's website.  James

(Jim) Rogers is probably responsible for the rapid

listing and relatively prominent standing of the site on YAHOO, GOOGLE and

NETSCAPE search engines: Jim quietly suggested the consistent wording used in

the footer on each page and provided the "robot friendly" text file we

use on the server to attract search engines. Jim has also scanned many of the

pictures shown in the retirement area and contributed to the many retirement

photographs..

James

(Jim) Rogers is probably responsible for the rapid

listing and relatively prominent standing of the site on YAHOO, GOOGLE and

NETSCAPE search engines: Jim quietly suggested the consistent wording used in

the footer on each page and provided the "robot friendly" text file we

use on the server to attract search engines. Jim has also scanned many of the

pictures shown in the retirement area and contributed to the many retirement

photographs.. Donald

(Don) Butt is credited with offering his Royal

Canadian Legion home as the place

Donald

(Don) Butt is credited with offering his Royal

Canadian Legion home as the place  Stan Fockner

Stan Fockner